Unveiling the role of fat molecules: a new perspective on infant leukaemia

How does fat content in leukaemia cells help them survive? Could targeting the fat be the key in treatments for infant leukaemia?

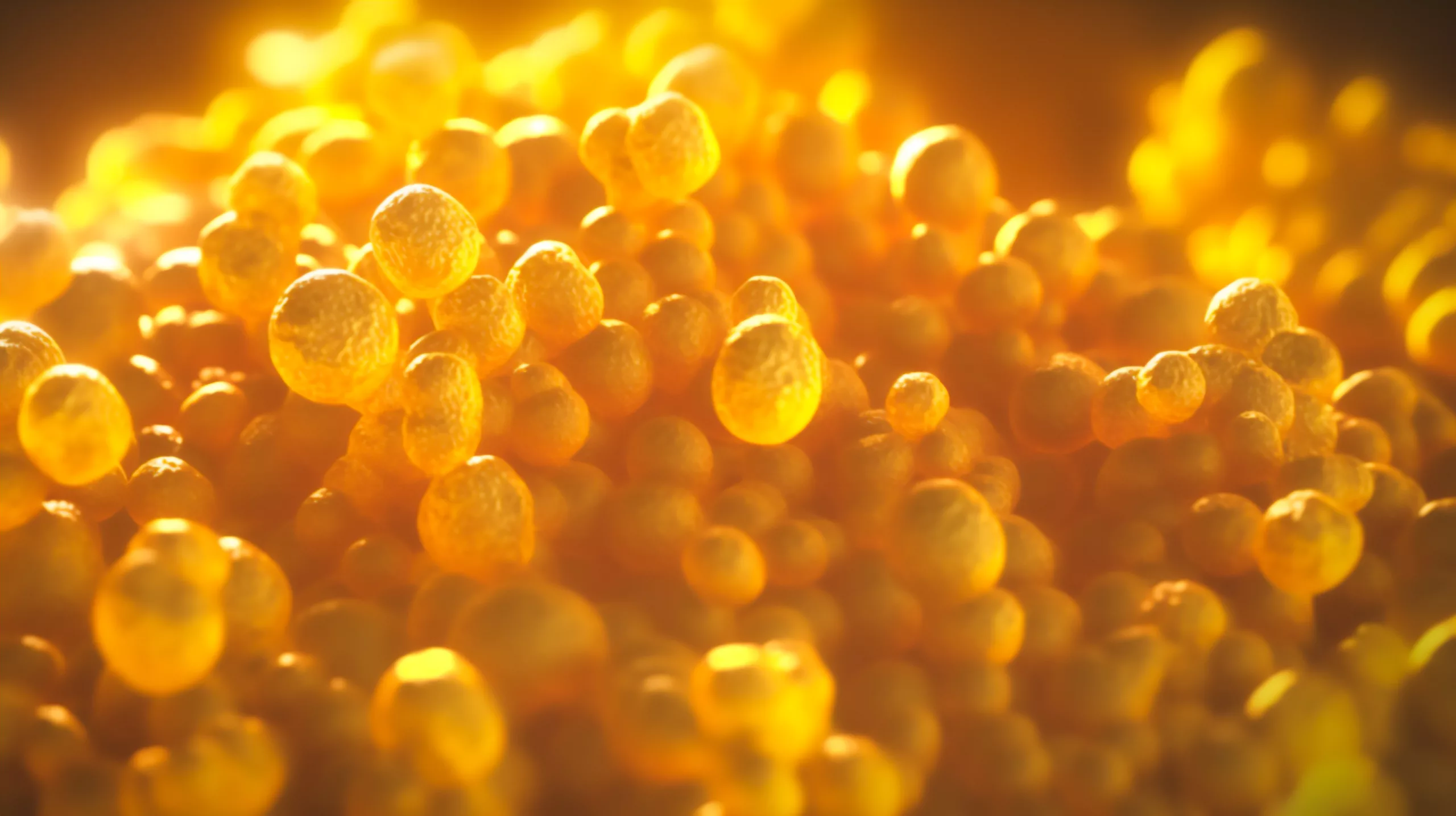

Two proteins were recently identified to regulate the fat content in infant leukaemia cells. This discovery highlights a new possible treatment option by blocking the proteins and how fat is regulated in the leukaemia cells. This innovative work, co-funded by Leukaemia UK and Worldwide Cancer Research is being conducted by Dr Katrin Ottersbach, a Professor of Developmental Haematology at the Centre for Regenerative Medicine at the University of Edinburgh, and her team.

The challenge:

While blood cancer is the most common type of cancer in children, acute leukaemia in infants (younger than 1 year old) is rare. Infant leukaemias make up 2-5% of children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) and around 10% of children with acute myeloid leukaemia (AML).

Infant blood cancer is different to blood cancer in older patients and has a very poor prognosis. The treatment options for infant leukaemia are the same as for older patients but these are very aggressive for such a vulnerable patient and have a worse success rate. Previously Dr Ottersbach and her team have shown that two proteins which regulate the fat content in cells are involved in infant leukaemia.

The science behind the research

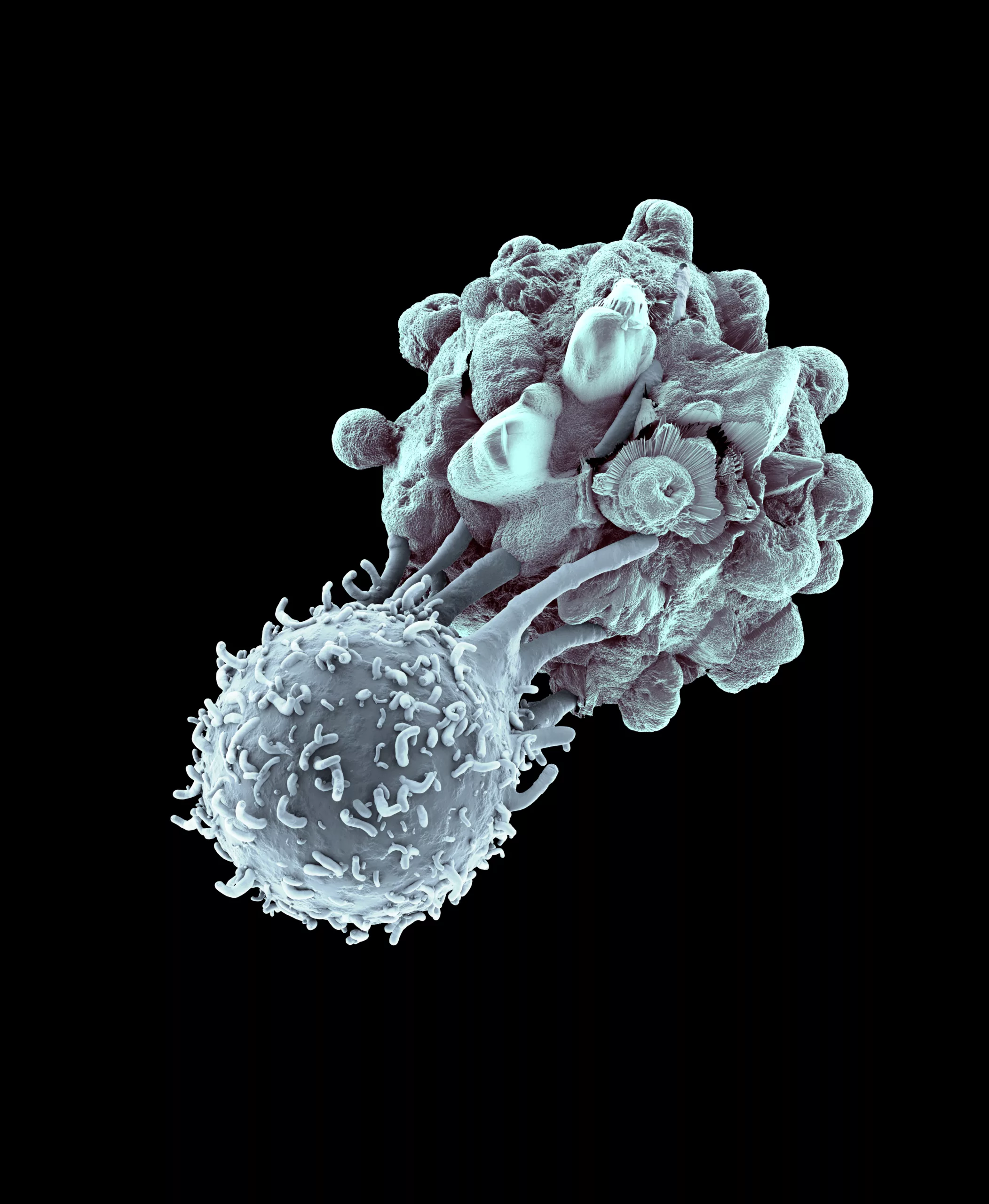

Leukaemia in infants (children under 1) begins to form prior to birth, originating in foetal blood cells. Scientists believe that this early onset contributes to its heightened aggressiveness, as foetal blood cells multiply faster compared to older children and adults and possess unique characteristics that facilitate cancer proliferation and progression.

“Understanding the unique biology of infant leukaemia is really key to developing kinder and more effective treatment. We are hoping that this new line of research may open up such new possibilities,” said Dr Ottersbach.

This project aims to understand the role of different fat levels in infant leukemic cells and how two specific proteins affect the disease process. The team is also exploring if the fat needs of the leukaemia cells can be targeted, which would allow for a new targeted treatment approach.

What difference will this research make?

The lack of progress in the treatment of infant leukaemia over the past decades highlights the pressing need for innovative approaches. Dr Ottersbach and her team are hopeful that their investigations will unveil previously unidentified weaknesses specific to infant leukaemia. This would allow for new treatment options to be developed, giving hope for kinder and less aggressive treatments for some of our most vulnerable patients.